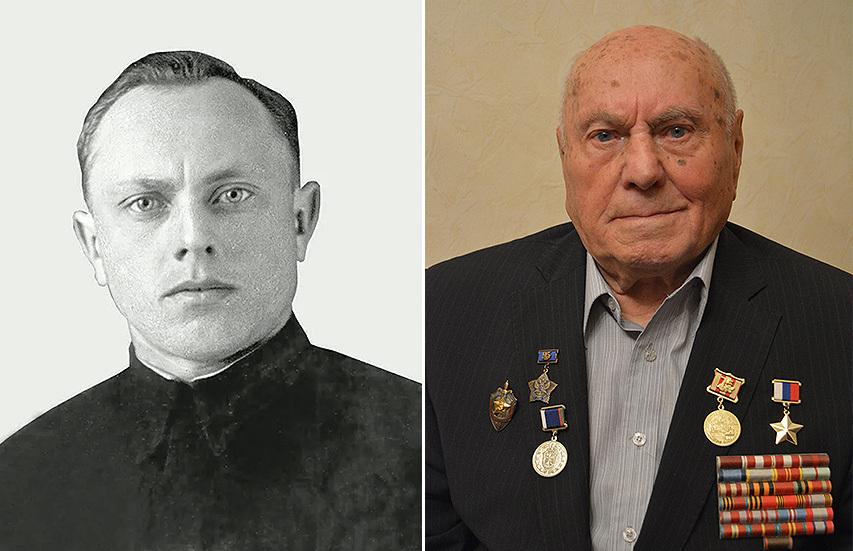

Legendary Soviet spy who saved Krakow from Nazi-made flood dies days after turning 103

A Soviet spy credited with saving the Polish city of Krakow from devastation has died in Moscow. His biography reads like a thriller novel, from battling Nazi invaders in Poland to training elite commandos in the 1980s.

Over his long life, Aleksey Botyan was many things. He was born in 1917, just as the Russian Empire was collapsing and shattering into pieces. His family lived in the territory that became part of Poland in the 1920s.

Fighting since day one

He might have lived as a village schoolteacher – his first choice of career – but in 1939 he was conscripted into the Polish Army just in time to face the Nazi German invasion. As an air defense non-commissioned officer, he spent the first days of World War II shooting at Junker warplanes.

Polish soldiers march disciplined in German war captivity, led by their officers. The officer on the left side of the column carries his saber - and the two German soldiers are unarmed. © Global Look Press / Scherl

Later, Botyan’s unit fled east and surrendered to the Red Army. The man escaped captivity and returned to his home village. Being a fugitive from the law in Stalin’s Soviet Union ended badly for many, but not for Botyan, who instead was enrolled into state security just a month before the Nazis invaded the USSR in June 1941.

Trained as a saboteur and clandestine operations expert, Botyan cut his teeth in intelligence, raiding German supply lines during the desperate battle for Moscow. After 1943 he was a deep cover agent, coordinating partisan forces in Ukraine, Belarus, Czechoslovakia and Poland.

Krakow undamaged

Poland is where some of Botyan’s most publicized operations took place, like the four-hour raid on the town of Ilza. The operation, by Soviet-friendly Polish resistance forces from the People’s Army, succeeded in freeing many captives and ransacking German stores for crucial supplies. But Botyan’s crowning achievement happened near Krakow in January 1945.

Parade of SS troops and police in Krakow on the first anniversary of the establishment of the general government, published 29.10.1940 © Getty Images / ullstein bild

The southern Polish city has the distinction of surviving the German occupation virtually unscathed. Unlike many other places in Poland and elsewhere, it didn’t see intensive street battles. Retreating Nazis didn’t even bother to demolish historic monuments or strategic sites.

The official Soviet explanation for this turn of events was that the Red Army conducted a lightning offensive towards Krakow and didn’t leave the Nazis time to lay waste to the city. The current prevailing Polish point of view is that the Nazis had no intention of damaging Krakow, which its propaganda declared an ancient German city.

Flooding averted

The retreating Nazis blew up a few bridges across the Dunajec and closed the Roznow Dam. The latter could have been followed with a devastating strike against the city; once enough water had accumulated, the dam would be demolished, causing a massive wave which would tear down Krakow. Botyan and his men are credited with thwarting the man-made disaster.

The partisan network under Botyan’s command learned where explosives required for such a large demolition work were stockpiled and staged a daring attack on the place. It was an old castle in Nowy Sacz, a city southeast of Krakow, which was obliterated just before the advance units of the Red Army reached the area. Botyan was awarded Russia’s highest title – Hero of Russia – for that operation in 2007.

The ruins of the castle of Nowy Sacz, 2010 © Wikipedia / Ffolas

Legend and fiction

Botyan’s wartime endeavors, after they were declassified in the 1960s, provided inspiration for writer Yulian Semyonov. His book ‘Major Whirlwind’ and its screen adaptation tell the story of a small group of intelligence agents sent behind enemy lines to prevent mass demolitions in Krakow. The titular character is partially based on Botyan, while aspects of the plot were inspired by his actual work.

His subsequent service in Soviet intelligence is far less publicized. Botyan had a long string of clandestine deployments in Czechoslovakia and Western Germany, and he was involved in teaching sabotage techniques to the elite Vympel commando unit. He retired from active service as a colonel in 1983, but kept in touch with the special services as a civilian consultant.

He passed away on Thursday, just three days after marking his 103rd birthday.

Source В Каунасе прошли памятные мероприятия в день освобождения города от немецко-фашистских захватчиков

В Каунасе прошли памятные мероприятия в день освобождения города от немецко-фашистских захватчиков

1 августа 2021 года в день 77-й годовщины освобождения города Каунаса (Литва) от немецко-фашистских захватчиков советник-посланник Сергей Рябоконь и военный атташе при Посольстве России в Литве Олег Давлетзянов совместн...

01 Aug 2021